Culture Jamming through Critical Theory Valentines

By Shannon Foss

On February 12, 2014, the radical philosophy blog Critical-Theory.com posted an article in their “Humor” section titled “25 Critical Theory Valentines to Rock Your World.” Calling Valentine’s Day an “orgy of consumption and heteronormativity,” the website offers 25 Valentines that can be printed out “in lieu of buying things” or purchased to support the Critical-Theory.com website (Wolters). The cards feature images of famous critical theorists along with phrases that evoke both Valentine’s Day tropes and the writings of the authors. I argue that both the integration of the counterhegemonic messages of critical theory into the genre of a Valentine’s Day card and the context of their production and reception allows these Valentines to operate as a form of culture jamming that resists the greeting card industry.

Statistics on Americans’ spending indicate scope of the consumerist tradition of Valentine’s Day. According to the National Retail Federation, in 2012 Americans expected to spend an estimated $17.6 billion on candy, balloons, paper cards, and other “tokens of love” (“Valentine’s Day 2012”). Not only this, but people desire to receive more than they want to spend – both men and women in relationships want their lovers to spend an average of $250 on the holiday, yet men say they plan to spend an average of $98 and women an average of $71. Despite the holiday’s associations with love, this corollary consumerist aspect of Valentine’s Day has become a bane to many. A1994 study found that the second-most prominent feeling that men associate with Valentine’s Day is one of obligation. Accordingly, Professor Angeline Close Scheinbaum and others explain the holiday through the framework of a psychological theory called “reactance.” While we may expect to be able to make free choices as consumers, when a society (or Hallmark) tells us to behave a certain way on a certain day we become resistant to it (Khazan). Though for many this resistance remains privatized or internalized, Critical-Theory.com’s Valentine’s Day cards exemplify it by engaging in an anti-consumerist action called culture jamming. Culture jamming refers to, “the act of resisting and re-creating commercial culture in order to transform society” (Sandlin and Milam 325). Examples include billboard “liberation,” anti-advertising “subvertisements,” and participation in DIY political theatre and “shopping interventions.” Asa Wettergren describes culture jamming as a form of “symbolic protest,” and defines it as the, “targeting of central symbols such as consumer objects, advertisement, logos, or other symbols vital to the discursive framing of the world that underpins corporate policy” (2). In this instance, I argue that Hallmark-style greeting card is the “consumer logic” that Critical-Theory.com appropriates in order to symbolically protest the material tradition of Valentine’s Day.

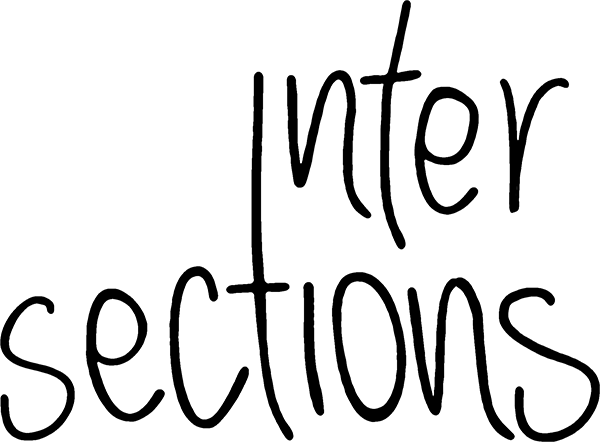

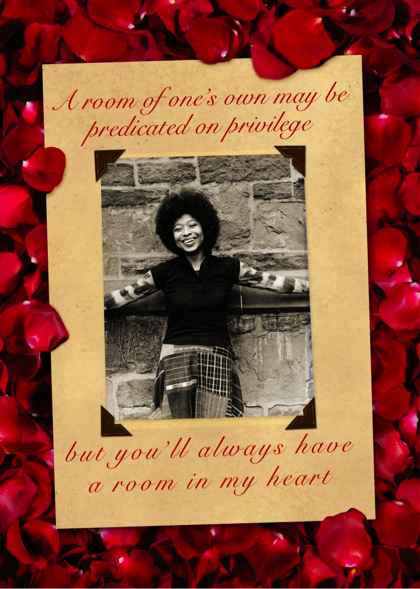

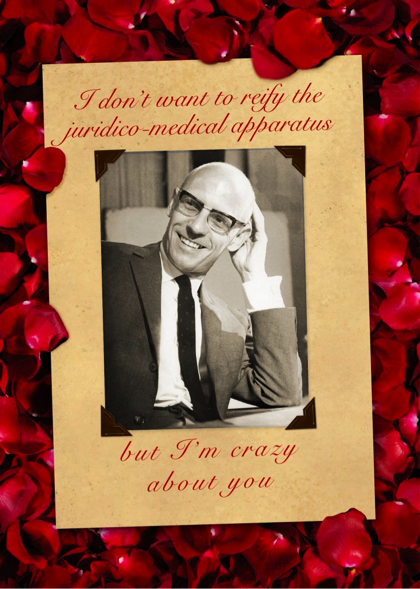

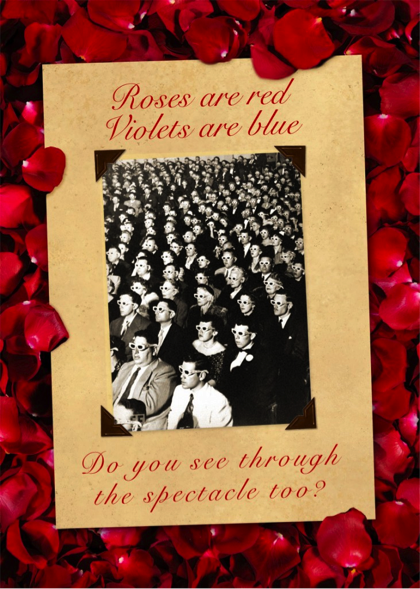

On one level, culture jamming occurs as the cards integrate critical theory into the aesthetic and discursive features of Valentine’s Day cards. As do traditional Valentine’s Day cards, the Critical-Theory.com cards use one of the holiday’s typical symbols – rose petals – to signify themselves as members of the genre. Likewise, the red color of the petals further fits with the aesthetic schema of Valentine’s Day. Within this bed of rose petals, though, Critical-Theory.com places an image of a theorist or an image associated with a theorist. For the purposes of this article, I examine four in particular. They portray, respectively, photographs of Alice Walker, Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard, and an image that evokes the writings of Guy Debord (Fig. 1-4). Because these theorists’ pictures are not usually portrayed on consumer merchandise, and because the writers themselves stem from an intellectual tradition critical of consumerism, placing their images amongst rose petals draws attention to the artificiality and constructedness of cards as “tokens of love.” Critical-Theory’s alternative cards create a sense of irony that stands in contrast to the typical seriousness of the holiday, thus resignifying the symbols of the holiday as a commentary on larger social and economic conditions rather than an expression of love.

Furthermore, the cards also integrate texts from the theorists into the typical platitudes expressed on Valentine’s Day cards. Alice Walker’s combines the theoretical ideas of “privilege” with the metaphor “room in my heart,” while Foucault’s uses the “juridicio-medical apparatus” in conversation with the idiom “crazy about you” (Fig. 1-2). Jean Baudrillard’s Valentine follows the address “Hey Baby” with the theorists’ concept of the “hyperreal,” and Debord’s utilizes the notion of the “spectacle” to finish the popular rhyme “Roses are red, violets are blue” (Fig. 3-4). This intertextual combination of metaphors, idioms, and theoretical jargon functions to create an emancipatory kind of humor by blending the greeting card genre and critical theory. Asa Wettergren explains that in the emotional regime of late capitalism, there exists a real-fake divide between two kinds of emotions: those which are cultivated in close relationships with a significant other and those which set the norms of participation in an anonymous social order dominated by the logic of consumption. While humor exists as a prominent component of the latter, she argues that, “the fun in protest embraced by jammers is to be perceived as qualitatively different from the fun offered by consumer culture. In other words, there is the authentic feeling of culture jamming and the false fun of consumption” (5). The Critical-Theory.com Valentine’s Day cards function like the former. They reclaim control over providing the means of pleasure by combining the aesthetic of greeting cards with images of theorists and by combining genre tropes with theoretical jargon to create a humor that stands apart from the typical one embedded in consumer culture. Aside from being funny, this calls attention to the constructedness of the cards as a whole. While these theorists may not have written directly about Valentine’s Day, the Critical-Theory.com cards culture jam by creating an implicit argument about how the authors’ ideas form a relevant commentary on the situation. Walker’s Valentine allows the audience to see the privilege implicated in constructions of romantic relationships, Foucault’s the ideological policing of society accomplished by the holiday, Baudrillard’s the way love fits into the simulacrum, and Debord’s the artificiality of representation in Valentine’s Day transactions. In this way, the integration of counter-hegemonic messages into the genre develops a social critique.

The cards’ conditions of production and reception also contribute to the message of their culture jamming. Part of the reason the cards act as an alternative to the mainstream greeting card industry is because Critical-Theory.com, a blog that identifies as writing about “radical philosophy,” created them. In this way, they do not participate in the same consumerist paradigm as traditional cards because they were not made by anyone even remotely affiliated with industry giants like Hallmark; nor did a single author construct them. The blog post, written by Critical-Theory.com creator Eugene Wolters, credits Taylor Grant for the template design and credits several individuals for writing the jokes on some of the cards (including the Guy Debord card), which further diffuses the locus of power associated with them. Admittedly, the cards are available for purchase on Zazzle to support the website, which on its face seems ironic; and in fact, some critics of culture jamming see its attempt to contest consumer society as, “ironically offering new sources of distinction for stoking the fires of consumer desire” (Carducci 122). However, I argue that this does not negate their oppositional status as an anti-consumer protest because the cards’ availability for purchase is a part of the humor associated with them. They are ironic, but because they are not written from a moral high ground they employ what Szerszynski calls “reflexive irony” – a “generalised ironic stance towards the world and oneself,” using the humor of the situation as a part of their purpose (Wettergren 6). What this humor still relies on, though, is a specific audience – one familiar with the tradition of Valentine’s Day, the tropes of greeting cards, and the authors and terms of the intellectual tradition of critical theory. Because of this, the cards can only counter the hegemonic influence of the greeting card industry for those are already familiar with the sociohistorical critiques in which these theorists engage. In this way, the capacity of the cards to culture jam is limited to individuals who might already be inclined not to engage in consumptive practices on Valentine’s Day. While this likely increases the salience of their message for the intended audience, it also means that this audience is neither extensive nor composed of the individuals most likely to buy into the critiqued practices.

Despite the limited scope of its audience, Critical-Theory.com’s culture jamming manages to resist the dominant greeting card industry by integrating images and texts from critical theory into the genre of the Valentine’s Day card and by creating a context of production and reception that allows for the development of an authentic kind of fun. Because of this, the size of the movement need not be conceived as making it inconsequential. As Kalle Lasn writes in Culture Jam, “We just need an influential minority that smells the blood, seizes the moment and pulls off a set of well-coordinated social marketing strategies ” (212). Using instances of Culture Jamming like these Valentines, Critical-Theory.com and websites like it can serve as the this influential minority. If they begin to coordinate their efforts with one another, their potential to resist the dominant forces in consumer society can be even greater.

Figures 1-4

- Figure 1. Alice Walker

- Figure 2. Michel Foucault

- Figure 3. Jean Baudrillard

- Figure 4. Guy Debord

Works Cited

Carducci, Vince. “Culture Jamming A Sociological Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Culture 6.1 (2006): 116–138. Web. 23 Feb. 2015.

Khazan, Olga. “Valentine’s Day Isn’t About Love—It’s About Obligation.” The Atlantic. 14 Feb. 2014. Web. 22 Feb. 2015.

Lasn, Kalle. Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America. New York: Eagle Brook, 1999. Print.

Sandlin, Jennifer A., and Jennifer L. Milam. “‘Mixing Pop (culture) and Politics’: Cultural Resistance, Culture Jamming, and Anti-Consumption Activism as Critical Public Pedagogy.” Curriculum Inquiry 38.3 (2008): 323–350. EBSCOhost. Web. 22 Feb. 2015.

“Valentine’s Day 2012: Americans Spend More On Valentine’s Day Than Halloween.” The Huffington Post. 14 Feb. 2012. Web. 22 Feb. 2015.

Wettergren, Åsa. “Fun and Laughter: Culture Jamming and the Emotional Regime of Late Capitalism.” Social Movement Studies 8.1 (2009): 1–1. EBSCOhost. Web. 22 Feb. 2015.

Wolters, Eugene. “25 Critical Theory Valentine Cards to Rock Your World.” Critical-Theory. February 12, 2014. Web. 22 Feb. 2015.

+ There are no comments

Add yours