Drawing Conclusions: Race and Representation in Two Local Museum Exhibits

By Anne O’Neill

The images in most popular cartoon art seem, at first glance, to be almost other worldly; two-dimensional basic lines, circus-bright colors, and exaggerated features that serve only to entertain us and provide temporary escape from the harsh limits of reality. A closer look, however, reveals just how firmly grounded cartoon art is in the world as we know it. Like other art forms, cartoon art is both a product and process of cultural creation, informing and (literally) illustrating our social schema. In this paper, I examine the ways in which cartoon art can be both reflective and affective of societal understandings of race, by using this lens to analyze two current local museum exhibits, Live on: Mr.’s Japanese Neo-Pop at the Seattle Asian Art Museum and the Northwest African American Museum’s Funky Turns 40: The Black Character Revolution.

At the Seattle Asian Art Museum, Live On presents an assemblage of artwork by Mr., the prominent Japanese neo-pop artist. The exhibit is an exploration of the artist’s response to his nation’s military and environmental traumas throughout the past century, and it comprises such various artistic forms as film, still photography, and found object/garbage installation. Most prominently featured, however, are Mr.’s oversized anime (cartoon) and manga (comic)-inspired acrylic-on-canvas paintings, hyper-colored works that repeatedly express two of the central concepts of Japanese pop culture: kawaii (“cute”) and moe (female adolescence, or literally “budding”).

In Japan, manga and anime are huge – some scholars claim that their ubiquity in Japanese society surpasses even the role that television plays in contemporary America. (Kawashima, 2002) With such profound cultural influence both within Japan and internationally (anime and manga are perhaps Japan’s most recognizable contemporary cultural export), it is worth asking what the images in anime and manga reveal to us about Japanese concepts of race.

Unlike in the United States, racial construction and categorization in Japan is not merely based on phenotype, but also incorporates notions of language, culture, citizenship, and behavior. Howard Winant states that the concept of race “emerged over time as a kind of world-historical bricolage, an accretive process that was in part theoretical but much more centrally practical.” (Winant, 2000, p. 172) When Western conceptualizations of race arose in the nineteenth century, the people of Japan were categorized under the racial designation “Asiatic.” In a practical effort by the Japanese to both assert dominance over other “Asiatics” (thereby justifying imperial practices), and allege developmental superiority over indigenous peoples and immigrants, the racial category of “Japanese” was claimed as superior and distinct. This ethnic/cultural notion of racial “Japaneseness” persists even today. Indeed, despite the presence of significant Ainu and Okinawan indigenous populations, who are considered to be ethnically, though not racially “Japanese,” as well as that of ethnically distinct Zainichi (resident) Koreans and sizable migrant populations, “the hegemonic image of Japanese society outside (and arguably inside) of Japan, has been of an ethnically, culturally, and linguistically homogenous place.” (Yamashiro, 2013, p. 147)

The kawaii and moe girls in Mr.’s Live On exhibit, as those in most manga and anime art, possess the phenotypical markers (saucer eyes, white skin, lightened/blonde/multi-color hair) that the Western eye commonly reads as “white.” If this is so, argues author Terry Kawashima, “it is only because [the] viewer has been culturally conditioned to read visual images in specific racialized ways that privilege certain cues at the expense of others and lead to an overdetermined conclusion.” (Kawashima, 2002, p. 161)

American racial construction is primarily visually based, and thus it can be challenging for the American viewer to look at the girls depicted in Mr.’s paintings and not read them as being “white.” Japanese racial identity, on the other hand, which evolved in part from a desire to distinguish one population from another phenotypically similar one, is constructed less around inherited physical characteristics and more so around conformity of culture, citizenship, and behavior. In this way, a blue-eyed and blonde manga girl reads as racially “Japanese” to the Japanese viewer, because she possesses the cultural markers of moe and kawaii, and lives within a genre that is firmly rooted in Japan. The Ainu and Okinawan populations within Japan, who are phenotypically similar but culturally separate, are perceived by most Japanese to be racially distinct. (Yamashiro, 2013)

If the depiction of “Japaneseness” in manga and anime is illuminative of the varying ways in which race can be socially constructed, it is also worth noting the absences within this racially homogeneous cultural product. Indigenous populations and ethnic minorities within Japan are rarely depicted within popular culture, and this lack of representation may add to their continued struggles toward social inclusion and economic and political parity. Media scholar George Gerbner coined the phrase “cultural annihilation,” which social scientists like Debra Merskin have used to refer to the absence of representation, underrepresentation, or negative portrayal of minorities in the media, a symbolic violence which does very real damage: “By presenting certain ‘types’ of persons or characters at the expense of others, and by almost never showing certain ‘types’ of persons or characters, the media not only reflect social values about the goodness/badness or preferability of some groups vis-à-vis others, but they also reinforce those notions in people who are exposed to these media.” (Klein & Shiffman, 2006, p. 178)

In this way, we can see how racial representations in the manga-inspired images in Live On, because they reinforce racial ideologies that reproduce inequality, are not merely social constructions, but also socially constructive.

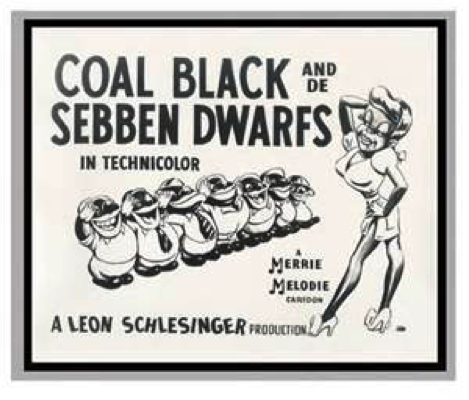

Gerbner’s concept of symbolic annihilation can also be applied to the derogatory representation of Black characters in American Cartoon animation in the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s. The overt racist stereotypes of the pre-Civil Rights era gave rise to popular cartoon caricatures of mammies, minstrels, and pickaninnies, among others; which in turn (mis)informed American cultural understandings. Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs, along with ten other animated shorts (“The Censored Eleven”), have in fact been deemed so offensive that Warner Brothers has refused to authorize their release to the public since 1968. (Slotnik, 2008)

Just as Debra Merskin’s Land O’Lakes “Indian maiden” reinforced American racial myths about Native Americans, Coal Black and other American animated cartoons served to reinforce demeaning racist ideologies about Black Americans. Merskin argues that these racist ideologies are not merely visually offensive, but that they serve to construct an “evaluative framework for perceiving otherness” that legitimates social inequalities. (Merskin, 2001, p. 161) Symbolic annihilation.

The Northwest African Museum’s Funky Turns 40 gives evidence that symbolic annihilation, however, can be turned around. This exhibit includes the original animation art of some of the most influential American animated cartoons of the late 1960’s through the 1970’s, the decade when Saturday morning television content began to feature Black characters in a realistic and positive manner.

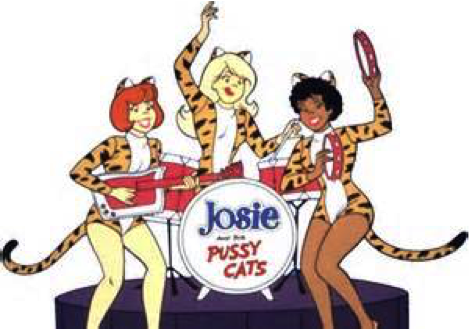

Original production cels and drawings from shows such as Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids, Josie and the Pussy Cats, The Harlem Globetrotters and The Jackson 5ive line the walls. With over twenty shows represented in all, Funky Turns 40 showcases many of the first animated Black characters who portrayed African Americans in a positive light.

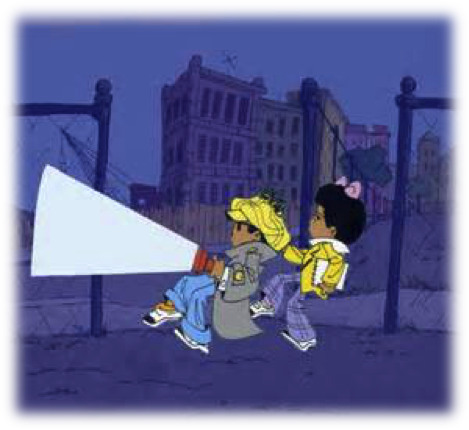

The cartoons of Funky Meets 40 originated in the Civil Rights era, when Black Americans were beginning to experience positive social mobility, and the signs of racial change within that time period are evident in the imagery: the beginning of integrated education is made apparent by the appearance of Valerie Brown in Josie and the Pussy Cats, Peter Jones in The Hardy Boys animated series, and Franklin Armstrong in the Peanuts gang. The new prominence of Black athletes in American sports is evidenced by cels from The Harlem Globetrotters and I Am the Greatest: The Adventures of Muhammed Ali. And the animated series The Jackson 5ive, as well as shorts from Schoolhouse Rock, and Sesame Street (including inner-city pre-pubescent sleuth Billy Jo Jive) all featured the newly-popular African American musical genres of funk and jive. These kaleidoscopic characters reflected America’s changing racial views, and reinforced positive Black stereotypes rather than negative ones.

According to Gerbner, among the myriad of meaning-making media, television may be especially powerful. His Cultivation Theory states that extensive and cumulative exposure to popular media has a profound effect on people’s attitudes, behaviors, and understandings of the social world. Additionally, because animated cartoons in particular are a medium that is primarily influential among young children in the initial period of development of their racial beliefs, and because exposure to this medium is repetitive and occurs over many years, cartoons effectively “crystallize young people’s race related beliefs and attitudes, while helping to shape relevant behaviors through the repeated and consistent race-related messages they provide.” (Klein & Shiffman, 2006, p. 167)

The 1960’s and 70’s cartoons featured in Funky Turns 40 grabbed hold of young American imaginations and replaced images of Black pickaninnies and jungle savages with those of superheroes, celebrities, and (perhaps most importantly) regular everyday relatable people. This exhibit provides ample evidence of one way in which the medium of cartoon art can and has been used as a cultural tool to invalidate earlier acts of symbolic annihilation through the creation and maintenance of positive racial ideologies in young viewers.

If at first glance we are tempted to dismiss popular cartoon art, whether it be the doe-eyed adolescent girls of manga and anime or the shabby and unsinkable crew from Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids, as “kid stuff,” we would do well to look more closely. The Seattle Asian Art Museum’s Live On: Mr.’s Japanese Neo-Pop and the Northwest African American Museum’s Funky Turns 40: The Black Character Revolution, reveal to us ways in which racial identity is both reflected and affected by the multicolored medium. Mr.’s blonde and blue-eyed representations of Japanese girls give evidence of historically-rooted societal differences in racial construction, as well as hint at the dangers of symbolic annihilation.

The positive representations of “Blackness” in the animated cartoon art of the late 1960’s and 1970’s not only present evidence of a means of subverting that symbolic annihilation, but also give visual clues about America’s evolving racial attitudes during the Civil Rights Era. Schoolhouse Rock can teach us mathematics and grammar, it’s true, but if we look closer, we may find that it is also instructive about the ways in which its underappreciated art form is both a product and process of racial ideological construction. No kidding.

References

Kawashima, T. (2002). Seeing Faces, Making Races: Challenging Visual Tropes of Racial Difference. Meridians, 161-190.

Klein, H., & Shiffman, K. S. (2006). Race-Related Content of Animated Cartoons. Howard Journal of Communications, 17:163-182.

Merskin, D. (2001). Winnebagos, Cherokees, Apaches, and Dakotas: The Persistence of Stereotyping of American Indians in American Advertising Brands. Howard Journal of Communications, 159-169.

Slotnik, D. E. (2008, April 28). Cartoons of a Racist Past Lurk on YouTube. The New York Times.

Winant, H. (2000). Race and Race Theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 169-185.

Yamashiro, J. H. (2013). The Social Construction of Race and Minorities in Japan. Sociology Compass, 147-161.

+ There are no comments

Add yours